| Posted August 31, 2018 | By Allan Effa, PhD, Professor of Intercultural Studies, Taylor Seminary, Edmonton, Canada | Categorized under Missiology and Praxis |

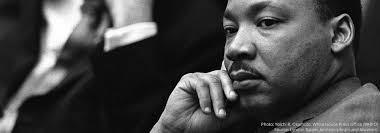

"Men hate each other because they fear each other;

they fear each other because they do not know each other;

they do not know each other because they do not communicate;

they do not communicate because they are separate."

- Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

This quote by Martin Luther King Jr. is at the top of my syllabus for the course on Intercultural Communication that I teach at Taylor Seminary. King was speaking about the problem of racism in America in the 1960s, but his observations apply to a myriad of contexts in our world today. Because we often find ourselves separated from people who are different and we do not share life with them on any kind of meaningful level, or engage in real heart-to-heart communication, we live in a culture susceptible to fear that sometimes even degenerates into hatred. People who have the harshest attitudes toward illegal immigrants, sexual minorities, the homeless, or followers of other religions, are seldom able to name anyone in their circle of friends who belongs to such categories. Stereotypes and misattributions are the fodder of fear and keep us from moving out of our comfortable ghettos into other people's domains.

This quote by Martin Luther King Jr. is at the top of my syllabus for the course on Intercultural Communication that I teach at Taylor Seminary. King was speaking about the problem of racism in America in the 1960s, but his observations apply to a myriad of contexts in our world today. Because we often find ourselves separated from people who are different and we do not share life with them on any kind of meaningful level, or engage in real heart-to-heart communication, we live in a culture susceptible to fear that sometimes even degenerates into hatred. People who have the harshest attitudes toward illegal immigrants, sexual minorities, the homeless, or followers of other religions, are seldom able to name anyone in their circle of friends who belongs to such categories. Stereotypes and misattributions are the fodder of fear and keep us from moving out of our comfortable ghettos into other people's domains.

I have taught a course on Understanding Islam numerous times here at Taylor. Two of the experiential assignments are to take a class trip to observe a prayer service at a mosque and for each student to spend at least one hour interviewing a Muslim about their practice and faith. That personal conversation, usually over a cup of coffee, is often the most transformational part of the course. We, in our divided world, need to spend time sharing life and conversation in order to dispel fear and hatred.

I remember the first time I had a conversation with a Sikh man. Sikhs had always intimidated me with their full beards, turbans and pajama-type clothing. So when the elderly Punjabi asked me a question at the bus stop I froze momentarily. Perhaps I feared he would bring out the little ceremonial dagger I heard they carry if I answered him inappropriately or that his poor command of English would make the conversation awkward. A few minutes into conversation and my pitiful stereotypes were destroyed. He had served in Her Majesty's Royal Air Force, spoke lovely British-Indian accented English, and had lived a fascinating life. Communication transformed fear and unknowing into warmth and potential friendship.

While the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Canada was concluding its hearings, an indigenous member of our church was invited to share her story on a Sunday morning. For fifteen minutes she relayed what it was like for her as a five year old to be taken away from her mother, placed in a residential school where the agenda was to make her think and act like a white girl, and then to be shuttled to several foster homes as a teen. Suddenly, the historical atrocities wore a human face and, when she was finished, the congregation stood and erupted into spontaneous applause that went on for a very long time. It was a time of healing and new understanding.

As we consider welcoming Syrian refugees or immigrants from other countries with cultures that are quite different from ours, there are a number of practical ways we can break down barriers and move from fear to understanding.

1. Be suspicious of your assumptions. Despite the poverty of their current situation, many refugees come with skills and education and at one time enjoyed a comfortable life in their homeland. Women who wear a hijab are not necessarily being oppressed by their husbands or made to feel like second rate citizens. They may be doing so out of respect and love for God.

2. Share hospitality by offering baked goods, gift cards but even better, by inviting them into your home to share a meal. Assure them beforehand that you will not be serving pork products or alcohol if they are Muslims.

3. Introduce them to common, everyday activities of North American life. Invite them to a high school basketball game, to visit a greenhouse, or just go for a walk. If they are new to winter sports, taking them skating or cross-country skiing can be a delightful time to laugh and play together.

4. Share practical tips on how to navigate life in their new land. My next door neighbours are from the Philippines and, during their first winter I saw them outside trying to chop thick ice on their sidewalk with a hammer and a plastic shovel. Much to their delight, I introduced them to my long handled ice chopper. It was a simple act, but it opened the door to conversation and sharing.

5. Be sensitive about inviting them to church. Newcomers may be eager to explore their new country and how Canadians or Americans worship, but beware of giving them a negative impression of Christianity before they have come to fully understand the culture. Remember that Muslims do not even use music in worship, so if your church worship is led by a rock-and-roll band and people pray to God in casual ways that would be highly disrespectful in other contexts, you might want to invite them to worship with you in a more traditional Christian service.

When Karen and I were missionaries in Nigeria, a Somali couple moved into a town a few kilometers away from our village. Abdi was working for an agricultural agency and came to meet us, confiding that his wife, Asha, was struggling with loneliness and looking for companionship. Abdi and Asha soon became dear friends. We shared meals, picnics, outings and many heart-to-heart conversations. They were practising Muslims, yet Abdi had done postgraduate studies in Wyoming and Asha had studied fashion design in Italy. We discovered that we had many things in common, despite our differences in faith and culture. Much to our surprise, we found greater joy in our visits with them than we did with some of our fellow missionaries. The oft-repeated saying is true, "There are no strangers, only friends you have not yet met" (W. B. Yeats).